Will Future Labour Shortages Imperil the BC Economy?

By Jock Finlayson

The critical role of human capital in today’s economy, the fact that many employers continue to report difficulties finding qualified personnel, and demographic forecasts pointing to a steadily aging population and slower labour force growth all raise questions about the future supply of skills. British Columbia is not immune to these concerns. A number of business leaders in the province have expressed alarm over the implications of current and potential skill shortfalls. A recent Conference Board of Canada report finds that existing “skills gaps” are already costing our economy close to $5 billion in foregone gross domestic product every year – an estimate which, if accurate, represents a substantial loss of economic value.1

Is there a risk that the province’s economy could be crippled by across-the-board shortages of employees?

Some Perspective

In thinking about this question, it is useful to begin by considering the wider economic context and the lessons that may be learned from the past. Worries about shortages of skills (or of workers generally) are not new. Attention tends to wax and wane with the state of the economy. The existence of temporary labour supply/demand imbalances in particular occupations, industries or sub-regions is not uncommon in a market economy, and should not be taken as evidence of an inherently malfunctioning labour market or poorly performing education and training systems. Economic forecasting is difficult, and predicting where the job market is heading is far from a simple task. Fifteen years ago few analysts anticipated shortages of data scientists, accountants, underground miners, heavy-duty truck mechanics, and other skilled tradespersons – yet vacant positions in these occupations have been hard to fill across western Canada in the last half decade or so.

When occupation- or industry-specific shortfalls in the supply of qualified workers do arise, they are usually temporary. As an empirical matter, serious and persistent shortages of workers have been rare in Canada. The reason is that labour market imbalances typically trigger institutional, policy and behavioural responses that, over time, serve to eliminate or mitigate the effects of shortages. If an economy or an industry has too few qualified workers, the operation of normal market forces should lead to some or all of the following outcomes:

- relative compensation levels increase for workers with scarce skills, which encourages more people to acquire the necessary qualifications and training;

- more young adults prepare themselves to enter occupations where demand is

predicted to be robust; - educational institutions modify programs and add capacity in high demand fields;

employers step up recruitment, retention and training efforts; and, - companies alter their production processes to reduce the need for hard-to-find skills. This may include outsourcing tasks or moving certain types of work to more labour-abundant jurisdictions – something that modern information and communication technologies readily enable.

In addition, governments concerned about skill or broader labour shortages can raise immigration levels, change retirement rules, and allocate more funding to education and training programs in areas where demand/ supply gaps are deemed to exist or are anticipated. Contrary to what some may believe, governments in Canada do respond to signals emanating from the labour market. The federal government has boosted immigration targets, revised immigrant selection criteria, raised the age of eligibility for Old Age Security from 65 to 67, and tweaked the provisions of the Canada Pension Plan to encourage later retirement. For its part, the BC government has prohibited mandatory retirement in most occupations and taken steps to bring labour market supply and demand into closer alignment with its 2014 Skills for Jobs Blueprint, which proposes to expand education/training capacity in selected occupations and fields of study and to reallocate funding within the postsecondary education system so that more resources are channeled to what provincial policymakers see as the priority needs.

In order for there to be a persistent shortfall in the supply of skills, something must interfere with or retard the normal market-driven economic, policy and institutional adjustment mechanisms. For example, the rules embedded in apprenticeship training systems may inhibit an industry’s ability to respond in a timely manner to changing market conditions. Young people may for some reason shun certain occupations or industries, even if they offer attractive career and job opportunities; many commentators and industry leaders believe this is a problem in the construction and industrial trades in Canada.2 Young people often lack reliable information on labour market and job trends – a gap that the provincial government is aiming to fill with its workbc web site (www.workbc.ca). Postsecondary institutions can be slow to add new spaces in high-demand fields due to cumbersome decision-making procedures, the difficulties of paring back low-demand academic programs, a paucity of instructors or equipment, or inflexible government funding policies. For these and other reasons, addressing skills shortages can be a protracted exercise, during which the affected industry (or perhaps the entire economy) performs below its potential.

Looking back, it is hard to make a case that Canada has suffered from a generalized “under-supply” of qualified workers. Until the early 1990s the number of Canadians with university degrees increased much faster than the number of jobs requiring such credentials. From 1971 to 1991, jobs requiring a university degree grew by 40 per cent, while the ranks of Canadian university graduates soared by 140 per cent. The US experience differed somewhat from that of Canada. There, growth in the supply of educated workers, at least until 2008, was more than fully matched by increases in the demand for such labour, with the result that Americans holding post-secondary credentials were more likely than their Canadian counterparts to enjoy rising relative as well as absolute employment earnings.3

More recently, Canada has experienced an increase in the number of “over-educated” workers – or at least of workers whose qualifications don’t match what the job market is demanding. A recent OECD survey finds that Canada is near the top among all advanced economies in the proportion of workers who report that they are “overqualified” for their current positions.4 Finally, the data on wage and salary trends in the last few years do not lend much support to the view that the economy as a whole is being held back by proliferating labour shortages. When a good, a service or a factor of production is in short supply relative to the underlying demand, we should see sustained upward pressure on its price. In the labour market context, “prices” are reflected in the pattern of real (inflation adjusted) wages and total labour compensation costs. In British Columbia (and Canada), these indicators show little evidence that labour is scarce relative to the demand for it, either at an economy-wide level or in most industries. Shortages of qualified employees do exist in some pockets of industry and in a few regions outside of urban areas, but not on a scale that adds up to a macroeconomic problem. It should be noted that in some other provinces, notably Alberta, the state of the labour market is different – with very low unemployment rates and greater challenges in finding employees.

Skill Shortages: An Emerging Business and Policy Issue

The above observations highlight the need to be cautious about forecasting skill shortages on the basis of anecdotal evidence, a snapshot of the current economy, or straight-line extrapolations of recent demand and supply developments in different occupations or industries. Market-driven adjustments in individual and firm behaviour, in wage and salary levels, in government policies and priorities, and in education and training programs will all play a role in narrowing any gaps that may emerge between the demand for and supply of skills. Having said that, a case can be made that the overall labour market in the coming decades will differ in important ways from what we have experienced in the past. Several demographic and economic trends suggest that shortages of appropriately educated and qualified workers are likely to be more common in the future. This means that the issue warrants ongoing attention from policymakers, employers and educators.

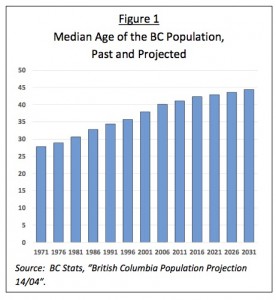

Demographics: It is common knowledge that our population is getting older. BC’s median age (Figure 1) presently stands at 41.7, up from 39 a decade ago and under 35 in 1991; by 2026, it is projected to reach 43.6. 5

Demographics: It is common knowledge that our population is getting older. BC’s median age (Figure 1) presently stands at 41.7, up from 39 a decade ago and under 35 in 1991; by 2026, it is projected to reach 43.6. 5

For present purposes, the focus is not on the total population but rather on the labour force, defined as the share of the population aged 15 and over that is employed or available to work. In the 1970s and 1980s, BC’s labour force grew rapidly, both because the population was increasing, but also because many more women were entering the workforce.6

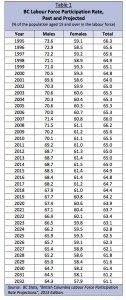

The share of the 15 and over population in the labour force, known as the participation rate, rose from the early 1970s until the mid-1980s. By the late 1980s, however, it had stalled out at around 67-68 per cent, and since then it has trended lower. (Table 1)

Looking ahead, forecasters predict a further slow decline in the participation rate, to somewhere near 61 per cent by 2030.7 The principal reason is that a relatively small share of people in the fast-growing 65 and over age group will be working, even though more older individuals are expected to remain in the workforce.8 In addition, many young people are devoting more years to education/training, thus delaying their entry into the workforce. Finally, today there is less scope than was the case 25 or 30 years ago to further raise female labour force participation rates, which have already risen to within a few percentage points of the average rate for males. Partially offsetting the demographic forces weighing down on labour force participation rates is the opportunity to increase participation among First Nations and other groups that traditionally have been less engaged in the job market.

In summary, over the next 10-15 years the average (and median) age of BC’s population and workforce will be rising, the overall participation rate is expected to gently decline, unprecedented numbers of workers will be retiring, and – relative to the province’s population – there will be proportionately fewer new labour force entrants. Based on this demographic picture, BC employers should be planning for an economic environment characterized by greater scarcity of skilled (and perhaps even entry-level) workers and longer time periods to fill vacant positions. The scenario sketched above of a gradually tightening labour market is consistent with the BC government’s official labour supply/demand outlook through 2022.9

In summary, over the next 10-15 years the average (and median) age of BC’s population and workforce will be rising, the overall participation rate is expected to gently decline, unprecedented numbers of workers will be retiring, and – relative to the province’s population – there will be proportionately fewer new labour force entrants. Based on this demographic picture, BC employers should be planning for an economic environment characterized by greater scarcity of skilled (and perhaps even entry-level) workers and longer time periods to fill vacant positions. The scenario sketched above of a gradually tightening labour market is consistent with the BC government’s official labour supply/demand outlook through 2022.9

Skill Intensity: Apart from demographics, other factors also support the view that skill shortages are apt to be more significant in the future. A large body of evidence indicates that: 1) the job market is becoming more demanding in terms of the minimal levels of education/skills needed to gain and retain employment; and 2) the demand for workers will be growing relatively quickly in many higher-skill occupations for which advanced education/training is necessary.

According to government forecasts, at least three-quarters of all job vacancies in the next decade will require some form of postsecondary credential (a degree, diploma, or technical/trade qualification). It is worth noting that the occupations in which demand in Canada has tended to outstrip supply in recent years include several in the professions, health care, various technician and technologist occupations, and management-related fields (Box 1).

Some analysts believe the supply of workers produced by the nation’s (and by BC’s) universities, colleges, technical institutes, and trades training systems is already woefully insufficient to meet present-day demand—although, as noted previously, at an aggregate level it is hard to find convincing evidence to validate this claim—and that the problem will get worse as the economy continues to grow and become more skill?intensive over time.10 The balance between labour supply and demand is relevant to British Columbia, because historically the province has relied on immigration to meet a substantial portion of the demand for skilled workers and has generally under-invested in the post-secondary education and skill-training infrastructure (this is less true today).

Looking to external sources to satisfy the demand for skills is likely to be a less viable strategy in the future—even though BC should continue to benefit from net immigration of working-age people.11

Growing Competition for Talent: Finally, heightened competition for talent, both in North America and globally, coupled with the growing mobility of younger, well-educated workers, also present challenges to employers in British Columbia. Consider that in the past dozen or so years, tens of thousands of working-age BC residents have moved to Alberta to pursue employment opportunities – often in the energy sector.

Another 30,000 or so British Columbians actually “commute” on a regular basis to work in Alberta, even though their home base remains in BC.12 (It remains to be seen how many of these current and former British Columbians “return” in the wake of the oil price collapse.) Within Canada, the competition for talent has been particularly evident in the skilled trades, the advanced technology sector, some segments of the academic marketplace, health care, and higher-level business management, but it is not limited to these sectors.

Some Implications

To the extent that British Columbia begins to experience significant shortages of skilled labour within the next 10-15 years, several consequences can be expected to follow.

- There will be upward pressure on pay and benefits as employers scramble to hire and retain workers with the requisite qualifications. Against this backdrop, public sector employers may be at a competitive disadvantage given ongoing fiscal restraint and rising compensation in the private sector for many types of in-demand talent—particularly at management and professional levels.

- Job-hopping, career shifting and interjurisdictional migration will become more common, as skilled workers take advantage of a greater range of career opportunities in BC and elsewhere.

- A growing number of employers will find it necessary to undertake more training and development of the existing work force—including of “older” employees (45+)—because of the difficulty of hiring qualified people from outside the organization.

- Particularly if wages are pushed up amid a tighter job market, businesses will have stronger incentives to economize on the use of labour by substituting capital and technology and using outsourcing where possible—trends that are already well-established.

- More partnerships will be forged between business and post-secondary institutions to (quickly) produce tailored educational and skill development programs designed to meet industry requirements.

- Pressure will continue to modify Canada’s immigration policies, both to increase the number of immigrants and to put greater emphasis on labour market needs in the selection process. The federal government has already been moving in this direction, and further steps down this path are likely in the future.

- New initiatives will be implemented to facilitate the recognition of foreign academic and professional credentials. Currently, many immigrants are unable to work in occupations for which they were qualified before coming to Canada. While some progress has been made in the area of foreign credential recognition, more mechanisms are needed to enable immigrants with qualifications in high-demand fields to proceed more quickly through the steps necessary to obtain certification to work in Canada. Improved and speedier acquisition of language skills—preferably before immigration occurs—is also essential given the poor job prospects facing individuals lacking a solid command of English or French.

- More job opportunities will become available for older workers who are prepared to remain in the labour force on at least a part-time basis. Overall, the incidence of part?time employment can be expected to rise as more people aged 60 plus stay engaged in the workforce. Employers, particularly in the public sector, should take a fresh look at their pension plans with a view to lessening disincentives for workers in their late 50s and early 60s to stay on the job.

Conclusion

A combination of population aging and modest economic growth means that BC’s labour market will be tightening over the next decade. Unemployment rates on average will be lower, many employers will find that it takes longer to fill vacant jobs, and wages/labour costs will be under greater upward pressure as the province enters an era of what can be described as “relative labour scarcity” after a long period of “relative labour abundance.” In this environment, concerns over skills gaps—including shortfalls in the supply of qualified workers and mismatches between the supply of skills and what employers are looking for – are likely to become more widespread.

The good news is that the normal adjustment mechanisms found in a well-functioning economy, including adjustments in compensation, individuals’ decisions about education and training, business practices, and public policy, can assist in addressing labour market imbalances. In the author’s view, BC is unlikely to experience an economy-wide “skills crisis.” But realizing the province’s economic potential at a time of significant demographic change and continued shift toward a knowledge-driven economy will require action by all parties—policymakers, business leaders, educators, and citizens—to improve BC’s skills base.13

Jock Finlayson is executive vice-president and chief policy officer for the Business Council of BC.

1 Conference Board of Canada, Skills for Success: Developing Skills for a Prosperous BC, February 2015.

2 This is not a new problem. Concern that too few young people were entering the skilled trades was widespread in Canada in the latter half of the 1980s.

3 A now classic treatment of the US experience is Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz, The Race Between Education and Technology, Harvard University Press, 2008.

4 Jock Finlayson, “The Plight of the Overeducated Worker,” Business Council blog, January 9, 2014 (this post links to the OECD study mentioned above).

5 BC Stats, “British Columbia Population Projection 14/04: Summary Statistics,” 2014. The median is the exact midpoint in the distribution – half of all people are younger than the median age and half are older.

6 BC Stats, “Evolution of the British Columbia Labour Force,” Business Indicators, October 2000.

7 BC Stats, British Columbia Labour Force Participation Rate Projections, 2013 Edition,” Appendix 1.

8 Participation rates among those aged 65 and older have been creeping higher, and BC Stats expects the trend to continue. But this will not be enough to offset the impact of large increases in the absolute and relative size of the 65 and over age group, most of whom are not (and will not be) employed.

9 Government of British Columbia, British Columbia 2022 Labour Market Outlook, 2014.

10 See the Conference Board of Canada, Skills for Success, op cit., and the sources cited therein.

11 The BC government projects positive net in?migration from other provinces as well as from international sources through the end of the decade.

12 Jock Finlayson and Ken Peacock, “Alberta’s Demand for Workers is Affecting the Labour Market in BC,” Human Capital Law and Policy, Business Council of BC, April 2014; available at www.bcbc.com.

13 A useful list of recommended actions is provided by the Conference Board of Canada, Skills for Success, op. cit., pp. 71?77.