Women in the Workplace: Then, Now and Tomorrow

By Jock Finlayson

The growing role of women in the workforce and the broader economy arguably represents the most consequential socio-economic development of the past 50 years.

Women Drive Real GDP

As more women have entered the formal labour market, the productive capacity of the Canadian economy has been augmented and average household incomes have risen. Indeed, increased “labour input”—more people working—has been the principal factor pushing up real GDP in Canada since the 1970s. Women account for the bulk of that increase.

Today in Canada, women comprise approximately 48 per cent of the labour force, up slightly from 46 per cent in 1999, but significantly higher than their 37 per cent share back in the mid-1970s. Men are still more likely to be employed, but the male/female labour force participation gap has narrowed over time. Soon, more than half of all the jobs in the country are likely to be held by women.

Among women aged 15 and over, approximately six in 10 were employed in 2013; in 1976, the comparable figure was just 42 per cent. The population aging that is starting to bear down on overall labour force participation rates is affecting women both genders, so the proportion of all women holding jobs will edge lower as the country becomes greyer. However, women’s contribution to the workforce will likely continue to increase over the next 10-20 years.

Women Still Clustered in Lower Third

Statistics Canada’s 2011 National Household Survey reports that they are most likely to be employed in three broadly defined occupational groups: sales and service occupations (27.1 per cent), business, finance and administration (24.6 per cent) and education, law, and government/community services (16.8 per cent).

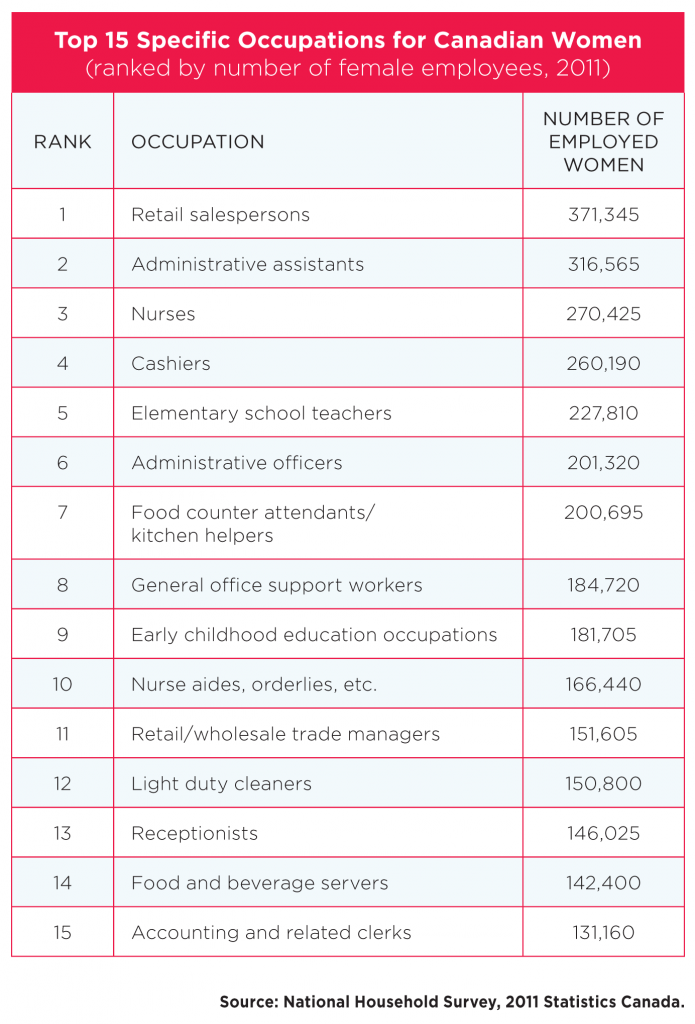

Despite gains in educational achievement, many working women are still clustered in relatively low-paying occupations. This serves to dampen average compensation for female job-holders collectively; it also explains the continued male/female disparity in average hourly pay. The top 15 specific occupations for women in Canada are listed below. A significant number of these fall in the bottom third of all occupations ranked by hourly compensation; a number also lend themselves to part-time work.

Improving “Human Capital” Faster Than Men

The impressive advances that women are making on the education front must be considered when assessing their employment and income prospects going forward. Between 1991 and 2011, the proportion of employed women aged 25 to 34 holding a university degree jumped from 19 per cent to 40 per cent, compared to a more modest increase from 17 per cent to 27 per cent in the case of men. In the language of economists, women are improving their “human capital” considerably faster than men.

The trend of rising female educational attainment is set to continue, as women represent a growing fraction of both current university/college students and recent graduates in a range of disciplines that often pave the way to high-paying jobs—including law, medicine, dentistry, architecture, business and finance.

Women have registered smaller gains in engineering and computer-related fields, but here too they are making inroads. The data show that girls generally outperform than boys in elementary and secondary school and this seems to be carrying over to the university and college level.

Skilled Trades an Open Opportunity

There are some areas of education and training where women still noticeably lag. One glaring example is the skilled trades. These are among the occupations that offer pathways to good jobs and the kind of middle-class standard of living that increasingly seems to be out of reach for young adults who lack any type of post-secondary qualifications.

According to Statistics Canada, women make up just three to five per cent of enrolments in registered apprenticeship training programs in the construction, electrical, industrial/mechanical, metal fabricating and motor vehicle and heavy equipment trades. That’s not good enough. Employers, educators and unions need to do more to encourage young women to consider skilled trades occupations and to create a supportive environment for those who choose to follow this route.

Jock Finalyson is the executive vice-president of the Business Council of BC.

(PeopleTalk Fall 2014)