The Silver Lining of Forced Change: Employees Can Work Remotely

The coronavirus pandemic that swept the world–and Canada–from February through May prompted governments to take extraordinary measures to shut down large parts of the economy, drastically curtail travel and day-to-day social interactions in a bid to slow the spread of the disease. In B.C., non-essential service businesses and schools were closed in March and employees of organizations permitted to stay open were advised to work from home if possible–and many of use still are working remotely.

Necessity is the mother of invention. Amid the pandemic, many businesses discovered that they could continue to function with most of their employees off-site. Such remote work can produce substantial cost savings due to the reduced need for office space and employee travel. And employees who work from home may also garner savings thanks to lower commuting and meal costs.

According to Global Workforce Analytics, a consulting firm, the number of “regular” at-home jobs in the U.S. has increased by almost 175 per cent since 2005, during a period when total payroll employment rose by less than one-fifth. Surveys indicate that a large majority of employees would value the opportunity to work from home at least some of the time.

Of course, telecommuting and other forms of remote work didn’t suddenly emerge as viable options because of the recent pandemic, but the crisis arguably has served to accelerate shifts in workforce management that were already under way.

Research from the U.S. Federal Reserve indicates that roughly one-third of employees can work remotely at least some of the time, but the picture varies significantly by industry and occupation. Well-educated knowledge workers typically have more scope to work off-site than people toiling in restaurants, nursing homes or retail outlets.

A new paper by economists from the University of Chicago takes a granular look at which jobs can be done from home. Focusing on industries, the authors estimate that 34 per cent of all jobs in the United States can be performed by employees from home, rather than at the employer’s place of business. By broad industrial categories, the largest shares of jobs that can be done from home are in professional, scientific and technical services (77 per cent); management (76 per cent); education (74 per cent); finance and insurance services (73 per cent); and information services (68 per cent). At the other end of the spectrum, relatively few jobs can be done remotely in industries like transportation and warehousing (18 per cent); construction (16 per cent); retail trade (14 per cent); primary resource extraction (eight per cent); and accommodation and food services (three per cent).

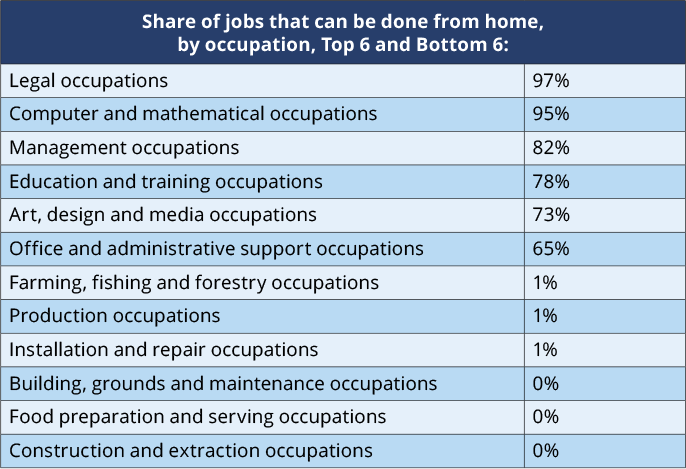

Slicing the data by occupation instead of industry, the same study finds dramatic variations in the feasibility of remote work. The above table lists the six occupational groups with the highest and lowest shares of jobs that can be performed from home.

The same research also reveals some interesting differences across urban regions in the extent to which jobs lend themselves to remote work. Affluent U.S. metropolitan areas with plenty of corporate head offices and universities and outsized high-technology sectors have proportionately more jobs that can be done from home than do cities with fewer head offices, academic institutions and big technology companies.

This points to another issue that is relevant when pondering the implications of the changing nature of work: the intersection with inequality. Workers in occupations that be performed fully or partially from home typically receive above-average earnings. The data summarized in the table generally underscore this fact. In the United States, the 34 per cent of jobs that can plausibly be done from home accounted for 44 per cent of total wages paid in 2018, suggesting a positive relationship between the likelihood that a job can be performed remotely and the pattern of wages. So it seems that many employees in lower-skilled occupations–particularly occupations that require manual labour and/or person-to-person contact with clients and customers–will be further disadvantaged in an economy in which a steadily growing fraction of all work is performed remotely.

Jock Finlayson is executive vice-president and chief policy officer with the Business Council of BC.

For the latest HR and business articles, check out our main page.

Reader Feedback

We want to hear from you!

Do you have a story idea you’d like to see covered by PeopleTalk?

Or maybe you’ve got a question we could ask our members in our People & Perspectives section?

Or maybe you just want to tell us how much you liked the article.

The door is always open.