Organizational Change & the Neuroscience Behind Why We Resist Change

“Understand that commitment to a major change is always expensive, and that you either pay for achieving it or pay for not having it.” — Daryl Conner

Change for the sake of change can disrupt us in ways unimagined — and most often unappreciated at the time — and yet it is the lifeblood of personal and organizational growth. Nonetheless, there are growing pains to be considered when affecting change on behalf of others.

Example: Who Moved My Chair?

One day a few colleagues and I walked into the office, chatting away about our long weekend, when we noticed that things seemed different. I got to my normal spot (you know the one near the bright windows) and saw someone else sitting there.

When I asked the person what was going on, all they could tell me is that that was their seat now. Confused, I went to my manager’s office where I found a line-up of employees with the same perplexed look as mine.

What we we found out via a rushed 30-second announcement was that the management team had decided to “change things up” to “add some spice to the office.” Without any preceding communication or obvious concern about our opinions or feelings, management told us to “get cozy in [our] new spots, and make new friends.”

Even A Small Change Has A Cost

Just like that, the routine I had grown so accustomed to was gone. No warning, no heads up for what was to come and no real concern. Instead of the usual loud chatter and welcoming greetings, the office became full of shaking heads and puzzled faces.

To be honest though, over the following days, I didn’t think much of it. Sure, it was out of the blue and not really managed as well as it could, or should have been, but, after all, it was just a desk change, right?

Well, I was wrong.

For reasons that I would come to understand later, this small, simple change, created chaos in the office.

Not long after, some employees started coming into work late and the office was silent most of the time. Our engagement survey showed the lowest scores we had seen in the past few years and employees would often say that the office was no longer the same.

In fact, according to many of us, the office culture we had grown so attached to — even though it certainly had room for change — was gone. It was something we knew and the change took us out of that cozy, safe space known as our comfort zone, making the potential benefits almost impossible for us to see.

Change really is the only constant in organizations and this is an example of it. Change happens all the time, whether we like it or not, and though it can bring positive consequences, change is often feared. In order for organizations and their employees to not only embrace, but survive these common situations, change must be managed and communicated closely and effectively.

A Failure to (Benefit From) Change?

Unfortunately, according to McKinsey, about 70 per cent of change efforts actually end up failing due to poor management.

Instead of reaping the benefits of change, organizations often experience project delays, missed milestones, low levels of engagement and productivity, reduced quality of work, and loss of valued employees. Even the smallest of changes can quickly become a crisis.

As a result, smart thinking says to have a talk before moving all the chairs in the office. With a bit of communication and solid change management, those moves can be magic after all — with no one losing out.

One of the biggest factors that negatively impact the change management process is our natural tendency towards comfort—towards what we know and what we are used to. We resist change, so much so that employee resistance is the number one reason most often cited for failed change.

But why?

What causes us to be naturally so repelled by change? What is going on up there in our brain? Neuroscience can help explain.

To Resist Change is Human

Neuroscience explains that resistance to change isn’t a conscious act. Instead, we resist change because of our evolutionary survival instinct and, as humans, we are inherently cautious about change. As soon as we encounter anything new or unexpected, the brain automatically assesses whether it presents a threat to our survival or a potential reward. This deeply rooted process happens at an unconscious level, and in less than a split second — we actually have no idea it is happening when it happens.

So, how is our brain impacted by organizational change?

Well, just like any other type of change, organizational change initiates certain triggers in our neurobiology, often creating a threat response.

Think back to changes you have experienced at your workplace. Perhaps there was a physical move, a role switch, or maybe even a new team added. What was your initial reaction? Did you enthusiastically embrace the change right away, or did it bring you negative feelings first?

Did you feel threatened and think that your role was no longer serving the organization? Did you feel scared? It is likely that these changes initially brought you some type of resistance, even if just for a few moments.

For some, this resistance is short-lived, while for others, it hinders their experience at work, and requires a great deal of time and effort to dissipate.

Knowing how we experience change, and that change is constant, how can we minimize this threat response that leads to resistance? It all starts with knowing and understanding these threat triggers, and, as per neuroscience, that we are motivated to move away from perceived threats and move towards perceived rewards. This is a crucial principle to keep in mind when examining change-related human behaviour.

Bring a SCARF to Change Management

The way an individual approaches or avoids change is described by David Rock‘s SCARF model of change. It identifies and describes status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness as the critical conditions activating threat responses in our brains.

- Status: Status is about an individual’s relative importance to others. In our daily lives, and in every conversation we engage in, we hold a representation of our status in relation to others, and this can affect our mental processes. When one’s sense of status goes up, the primary reward circuitry in the brain is activated; however, the perception of a potential or real reduction in status can generate a strong threat response in our brains. Because of this we often unconsciously assess our standing in relation to others around us. Think back to a time when a new team member joined your team, or when a coworker took over one of your projects. How did you feel?

- Certainty: Certainty is about being able to make predictions about the future. It’s about familiarity. When we use our brain, we tend to use the least amount of energy possible (a phenomenon known as the Law of Least Effort) and, as such, we rely on pre-existing patterns to make future predictions about our surroundings. In a state of deep uncertainty, there are few or no preconceived patterns. This requires the brain to use much more energy to make sense of the environment, manifested by an increased uptake of glucose. Given this mentally taxing byproduct, when faced with uncertainty, we biologically retract from the change in order to conserve energy.

- Autonomy: Autonomy is an individual’s perception of having control over events—the ability to self-determine actions and to have a choice. If employees have some measure of choice in regards to change, they will be more likely to embrace and move towards it. When an employee’s perception of control is jeopardized, this has a domino effect on the individual’s sense of certainty. Therefore, if there is a perception of lack of control, this will trigger a sense of uncertainty, leading to an avoidance response. A reduction in this sense of autonomy instantly triggers a threat response in our brain. Autonomy is not just a perk, it is a biological need.

- Relatedness: Simply put, relatedness is a sense of social belonging. It’s the foundation of all groups. Relatedness involves a feeling of safety with others—deciding whether others are friend or foe. Employees who feel as though they are going through change alone are more likely to avoid it. This doesn’t just happen in organizations, but also in our everyday lives. We are more likely to accept change when we know others are able to relate.

- Fairness: As humans, we have a great biological need for fairness, and unfair exchanges generate a very strong threat response. This isn’t just the case for humans either! Studies show that other animals, such as monkeys and dogs, show extremely negative reactions to unfair situations as well.

The way an individual approaches or avoids change is described by the SCARF model of change. It identifies and describes status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness as the critical conditions activating threat responses in our brains.

Having explored the dimensions — status, certainty, autonomy, relatedness, and fairness — in the SCARF model, questions remain. How can we use this model to navigate organizational change in a more effective way while minimizing threat responses?How can we effectively manage organizational change while keeping our neurobiology in mind?

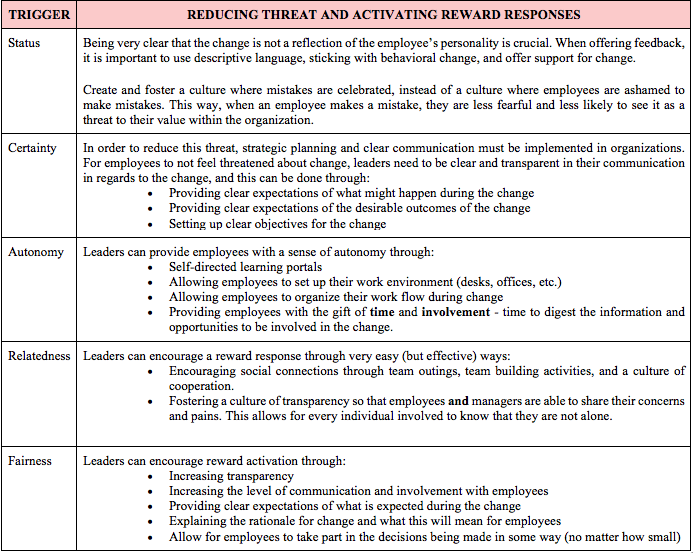

The table below illustrates easy tactics that can be used to transition individuals from a threat-avoiding mindset (change resistant) to a reward-approaching mentality (change receptive).

Change in Retrospect

We have all experienced resistance to change despite the positive consequences it can bring. Though I couldn’t understand at the time, I can now see how a small change in the physical space or the disruption of a routine can significantly impact an organization. It’s not so much about the change itself, but more about how it is managed and embraced. Fear, threat, avoidance—these are all the characteristics I saw in my co-workers’ faces, the elements that lead to chaos, then forward.

There are many ways to look at change. With its constant presence in our work environments, perhaps the most important way is to see it through our employee’s eyes.

How can we support and aid employees to welcome change and thrive in unpredictability, rather than reject change and suppress growth? How can an organization ensure that their efforts don’t fall into the 70 per cent of failed change category? A little bit of empathy can go a long way.

Gabriela Freitas is an employee engagement consultant and researcher at Jalapeño Employee Engagement in Vancouver, BC. She has a BA in Psychology from the University of British Columbia and is currently pursuing her Master’s degree in Organizational Psychology at Adler University, with a focus on empathy and employee engagement. Jalapeño is bringing their vision of a better workplace to life by developing a powerful survey platform paired with professional services to maximize employee engagement.

For the latest HR and business articles, check out our main page.